This is a discussion of a woman, an ordinary woman who participates in the everyday and commonplace acts of life. As she re-views (reminiscences) about her present, past, and future. This collaboration of, and interdependence between the visual and the verbal, forms an autoethnography of a woman’s life and explores a still developing, still evolving selfhood.

Featured Post

Linda Rader Overman is so proud of her former student Natalie Grill who was a winner of the Oliver W. Evans Writing Prize in Fall 2023--Well done!!

A Comparative Analysis of Spiegelman’s Maus II and Oster’s The Stable Boy of Auschwitz It has been nearly eighty years since that decis...

Tuesday, October 24, 2017

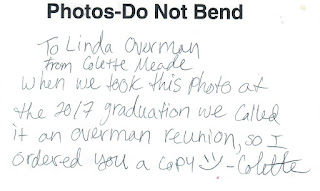

Linda Rader Overman celebrates a student Overman Reunion Spring 2017

It is with gratitude and joy that I salute some of my former students who graduated from CSUN Spring 2017. From L to R.

Jessica Funtes, Colette Meade, Diolorant Chery, Lucas Gomez. I know you will all shine in your teaching professions and bring the same happiness to your students that you brought to me as students.

Well Done.

Sunday, July 9, 2017

Part One: What do you do when the daughter you cherish follows an unimagineable path?

I'm the mother of a drug addict. There, I've said it.

Now what?

I stare at her five year old picture, taken over three decades ago. She wears a lace white broad brimmed hat--mine.

Jewelry, collected from her grandmother and my drawers, hangs 'round her little neck against the blue flowered pattern and white linen bib of a favorite party dress. One hand rests in the other showing the array of colored plastic bracelets, more than ten, on her right arm.

Her long brown hair frames a chubby cheeked child who we adore. Her green eyes look camera right. The future awaits.

The future her father and I hoped for, however, is not the future she chose.

Fashion, in all shades, shapes and sizes, she loved. The clothes, the designers, the fabrics, the shoes, the clients, that world engulfed her. And she drank it in every step of the way.

Working at a nearby mall, she started out as a greeter in a small boutique until her sales abilities took her up the ladder while attending a private catholic high school. Later, she attended FIDM and worked hard graduating Cum Laude.

Working in one high end boutique after another until she started her own clothing line drove her creative passion.

Choices in men created diversions some for the better, some for the worse, mostly the worse. Yet, she survived never losing her love of selling, styling and making clients happy.

A layoff changed her direction, at first. The need to survive enabled her own line creation, but that road became fraught with stumbles: one season she had buyers and the next season she had none.

More work in more small high end boutiques continued. She always outgrew them and ended up in a more corporate controlled boutique with hopes of moving up within that structure. She did and she didn't.

Throughout this journey, drugs became an easy go to. Following college, she stomped through her twenties and her behavior fueled by Marijuana, Ecstasy, Cocaine, changed her. We never knew who or what to expect at family gatherings. She still managed to keep her job and keep her sales figures high, high, high.

We stopped communicating with her as her drug dependency fashioned a stranger we no longer recognized.

A year later her father was diagnosed with a cancer no one knew much about and there was no treatment, no cure.

We called her back to our home since we weren't sure how long my husband had left.

That was a mistake. . . .

and to write any more at this time is just too too painful.

Now what?

I stare at her five year old picture, taken over three decades ago. She wears a lace white broad brimmed hat--mine.

Jewelry, collected from her grandmother and my drawers, hangs 'round her little neck against the blue flowered pattern and white linen bib of a favorite party dress. One hand rests in the other showing the array of colored plastic bracelets, more than ten, on her right arm.

Her long brown hair frames a chubby cheeked child who we adore. Her green eyes look camera right. The future awaits.

The future her father and I hoped for, however, is not the future she chose.

Fashion, in all shades, shapes and sizes, she loved. The clothes, the designers, the fabrics, the shoes, the clients, that world engulfed her. And she drank it in every step of the way.

Working at a nearby mall, she started out as a greeter in a small boutique until her sales abilities took her up the ladder while attending a private catholic high school. Later, she attended FIDM and worked hard graduating Cum Laude.

Working in one high end boutique after another until she started her own clothing line drove her creative passion.

Choices in men created diversions some for the better, some for the worse, mostly the worse. Yet, she survived never losing her love of selling, styling and making clients happy.

A layoff changed her direction, at first. The need to survive enabled her own line creation, but that road became fraught with stumbles: one season she had buyers and the next season she had none.

More work in more small high end boutiques continued. She always outgrew them and ended up in a more corporate controlled boutique with hopes of moving up within that structure. She did and she didn't.

Throughout this journey, drugs became an easy go to. Following college, she stomped through her twenties and her behavior fueled by Marijuana, Ecstasy, Cocaine, changed her. We never knew who or what to expect at family gatherings. She still managed to keep her job and keep her sales figures high, high, high.

We stopped communicating with her as her drug dependency fashioned a stranger we no longer recognized.

A year later her father was diagnosed with a cancer no one knew much about and there was no treatment, no cure.

We called her back to our home since we weren't sure how long my husband had left.

That was a mistake. . . .

and to write any more at this time is just too too painful.

Monday, July 3, 2017

Linda Rader Overman is proud and honored to accept this nomination from her students in Adolescent Literature this Spring of 2017 at CSUN.

I am deeply humbled.

I am deeply humbled.

Saturday, January 7, 2017

Linda Rader Overman is very proud of her students' critical film reviews of Mustang by director, Deniz Gamze Ergüven.

The film Mustang is both a coming of age tale about five sisters and the

strife they encounter through female adolescence growing up in Turkey, and a

cautionary tale about freedom of expression, and the price paid for breaking

the status quo. Sonay, Selma, Ece, Nur, and Lale play the role of five sisters

that take the audience through their journey of overcoming adversity, often

without much of any positive outcome. One by one the audience witnesses their

lives change within given relationships not just with each other and members of

their own family, but the external conflict between themselves and society as a

whole. The film sparks a conversation about the role of women in many nations

where religion takes precedent over individualism. Therefore, the film Mustang is reminiscent of a teenage

slasher horror movie, masquerading as a coming of age tale of female

individualism overcoming adversity.

Female sexuality is the driving

cognitive metaphor throughout much of the movie. There are two basic elements

of the film that guide my perspective on the film: parallelism and motif. The

film begins innocently enough with the five sisters mentioned playing in ocean

waters with a group of adolescent boys. Physical contact is represented in a

very child-like sense, with no sexual overtone or sexual contact expressed

during the opening scenes. This setup establishes the mood and characterization

that carries the rest of the film. It is necessary, for its ability to show the

innocence of the five sisters all living out an idyllic afternoon among

friends. The motif among these scenes, the binding connection symbol, is the

ocean. The ocean then represents the metaphor between nature and man’s

dominion.

The ocean is shot at a wide angle,

with close ups involving the girls all laughing in its bliss and among the

boys. It is almost as if the ocean acts as a barrier to the outside world

around them, and a blanket that encompasses both the girls and the boys at

close physical proximity. There’s already a strange feeling of tension, that

part of life where girls and boys start to mature and blossom into women and

men, and is represented with some of the older sisters, particularly with the

likes of Selma and Sonay. They are carried atop the shoulders of boys, the

ocean waters drenching them repeatedly as the men bounce them up and down above

their heads with the ebb and flow of the waves. It represents the sexual coming

of age between the two eldest sisters, whose physical proximity to the boys are

almost natural for girls their age with developing hormones, with the sensation

of dampness and the bobbing between shots giving the audience the allusion

about sex.

After their trip through the garden,

the introduction of the film’s parallelism is first seen. The ocean scene and

the garden scene are similar with their bliss and naïve quest to explore the

nature of life around them, and thus an inner journey to search for their own

identities. What separates the two is the man with a shotgun who jolts the

women back into reality, of diving into areas they should not be wandering. The

entire scene sets up the second act of the film, and the consequences for

flying too close to the sun so to speak, and even representational of the fall

of Adam and Eve in the Garden when they became too self-aware of their Original

Sin. In this case, the Original Sin is the lack of concern for obeying status

quo, and allowing themselves to partake in open public physical interaction

with young boys.

From here on out in the film, the

idea of premarital sex, or any physical lewd act for that matter, is discussed

openly. It allows the audience to see the main external conflict right in the

open without any hesitation: Their virginity, their chastity, their bodies and

their vaginas are not their own. On the contrary, they are vessels for men, for

society, and for their future husbands now and forever. While the beginning and

the very end of the film becomes a story of personal growth and overcoming

adversity for one particular character, the main protagonist and the youngest

sister Lale, it then turns into a cautionary tale for all the other sisters.

Maureen Medved, a famed scholar who

analyzed the subliminal messages of the film Mustang mentions in her article, “the innocent freedom they

experienced before their imprisonment was a cruel illusion” (Medved 47). In

almost every teenage slasher film, there are “tropes” commonly mixed in for the

audience to analyze. A group of teenage characters arrive, stumble upon a

remote area they shouldn’t have wandered, and are then systematically killed

off one at a time usually because of their sexual promiscuity, drug use,

tattoos and piercings, and anything else that symbolizes individuality and acts

seen as negative by society and the status quo. The heroine, if there are any

survivors, is always the chaste and innocent girl where through her sexual

repression, defeats her antagonist by expelling all her tension through

physical action. Mustang turns into a

horror movie, with clever variations disguising some of the more overplayed and

clichéd stereotypes and tropes.

Our five main characters are all

introduced, each with their own personalities and yearnings for personal growth

and freedom. Each are thrown into naïve amusement during the opening scenes at

the ocean and through the garden. As the film progresses, they are marked by an

elder neighbor who spills the beans and begins to change the course of their

lives forever. Uncle Erol, their guardian along with a multitude of elderly

aunts and female relatives, scorn them for even thinking of unleashing their

sexual promiscuity. They are all locked up in a house that slowly but surely

becomes more and more securitized, like countless infamous tales of a Haunted

House Story where no one can leave. Their sexual promiscuity ends up being

their downfall when the elders think it is time to sell off their girls to the

highest bidders, with not even a word of consideration from the sisters

themselves.

The wedding scene represents an

excellent example of parallelism, where one sister Sonay is beyond overjoyed to

be engaged to the man of her dreams, while another sister, Selma, is openly

displeased. Her “virginity check” is a time for catharsis for herself and for

the audience, to analyze why she states her message of how she has slept with

many men even though her hymen seems to say otherwise. It’s as if she’s

wondering why she is being punished with this miserable life and circumstances

outside her control, and why she simply cannot enjoy life and individuality.

She is already dead, “killed” on the inside and has been for some time. Sonay

seems to believe that she has “won,” that because she is with the man of her “dreams”

she will be just fine and “we” as an audience never know what ends up of her

fate and whether a happy marriage is in the works and maybe that is all she

needs. But then again, how do any of us know if a happy marriage to a loving

spouse is all we’ll ever need as the years go on?

Ece is the next sister on the

chopping block, who suffers the ultimate doom. It is revealed that Uncle Erol

has been molesting her, stealing away her innocence. In rebellion, she allows

herself to have sexual relations with another boy in the backseat of her

Uncle’s car very dangerously and in public. Her exposure to sex has always come

at a negative, and soon enough, she ends up taking her own life with a gun. Since

sex is taken by force, and innocence is robbed, the effects on Ece are

devastating and comes at a heavy price, along with the burden for those suffering

that hardship. Maral Erol, a researcher on Turkey’s medical arena, states that,

“Nearly half of forensic physicians

in Turkey conduct virginity examinations for social reasons despite beliefs

that such examinations are inappropriate, traumatic to the patient, and often

performed against the patient's will” (Erol 55). Even

if the girls get away with certain acts of promiscuity, society will always

find a way to keep them in check, scaring them into forever forcing them to be

pure, or suffer the consequences beyond your imagination.

Lale’s

last sister in the house, Nur, is also being taken advantage of by Uncle Erol.

Through a cunning plan, the two sisters finally act against society and their

elders and find a way to escape the horrors and trauma of what was to be their

futures. Lale is in control, as the innocent and still a chaste girl who takes

over the wheel of a car and drives off – somewhere…anywhere. Our main

protagonist, our heroine, our leading lady who defeats her monster ends up

escaping and even manages to survive with one of her sisters, but do they drive

off into the sunset? Is it a happy ending to know that all of Lale’s other

sisters, except for Sonay who accepts her fate to be a housewife for better or

worse, are doomed one way or the other and punished more or less by the use of

either sexual desires or sexual misdeeds? How far can they go behind the wheel

of that car, at their age, in an entire nation designed to shackle them? The

movie has another classic horror movie inspired ending; our main heroine has

survived, for now, but the boogeyman is still out there lurking and stalking.

And if it’s not their Uncle, it’s their aunts, or their neighbors, or the

police, or anyone at all in the country of Turkey.

Analyzing

the movie therefore is like summarizing any teenage slasher film. A group of

young adolescents think they are all alone, with the freedom to express

themselves any way they see fit. They are soon “found out” by a force, an

unstoppable entity that stalks them at every turn. They are isolated, secluded

from others in a physical “location” they cannot escape from and weld shut from

the outside. One by one, sex proves to be their downfall until finally a brave

chaste heroine makes a daring escape that expels the antagonist once and for

all out of their lives. Before the film concludes, and as they are driving off

into the unknown, it highlights their emotional growth and spiritual journey, and

hints that the audience shouldn’t necessarily assume a “happy ending” if all of

Lale’s sisters are gone or negatively affected, and the Boogeyman is still out

there in some form or another trying to catch them. The title of Mustang, is in reference to Lale, the

brave steed who gets away by finding her inner strength to confront the evil

fate that stands before her. The one, lone chaste warrior who at least for a

brief while, has the chance to get away.

Works

Cited

Ergüven, Deniz Gamze, director. Mustang. Cohen

Media Group, 2015.

Medved, Maureen. "Mustang." Herizons Summer 2016: 47.

Expanded Academic ASAP. Web. 7 Nov. 2016.

Erol, Maral.

"From Opportunity to Obligation: Medicalization of Post-menopausal

Sexuality

in Turkey." Sexualities, 17.1-2 (2014): 43-62.

in Turkey." Sexualities, 17.1-2 (2014): 43-62.

Deniz Gamze Ergüven’s Mustang and the Fight for Control Over

Women’s Bodies

by Colette Meade

by Colette Meade

In

America, mustangs are feral horses that have escaped captivity are adapted to

the conditions of the wilderness (Schafer). Mustang is a

2015 Turkish film directed by Deniz Gamze Ergüven where young women also fight

to escape captivity. The film centers on the story of five orphaned sisters

growing up in rural Turkey in the early 2000’s. The film stars Güneş Şensoy as

Lale, Doğa Doğuşlu as Nur, Elit İşcan as Ece, Tuğba Sunguroğlu as Selma, and

İlayda Akdoğan as Sonay. At the beginning of the film, the sisters are shown

playing innocently in the ocean with male classmates. Unfortunately, this is

interpreted as a sexual offense by members of their community, and their

surrogate parental figures, a grandmother and uncle, Because of this incident,

the older sisters Ece, Sonay, and Selma are subjected to “virginity tests,” all

of the girls are not allowed to return to school, and their home is converted

into a prison that they are rarely allowed to leave. Meanwhile, their

grandmother begins cooking and sewing lessons with the sisters as they are set

up in arranged marriages one by one. In addition, it is revealed that their

uncle is molesting first Ece, and then Nur.

Ergüven intended to convey a powerful feminist message against

patriarchal oppression in her film Mustang;

she conveyed this through strategic plot points including the reaction to the

girls frolicking with their male classmates, Nur’s molestation, and Ece and

Lale’s acts of rebellion.

There

is a powerful message regarding women’s role in a patriarchal society in the

film Mustang. Patriarchy is defined

as “a social structural phenomenon in which males have the privilege of

dominance over females, both visibly and subliminally [which is] manifested in

the values, attitudes, customs, expectations, and institutions of the society”

(Darity). Turkey has a long-standing

tradition of being a rather patriarchal society despite some modern

improvements over the years. The

Encyclopedia of Women & Islamic Cultures describes this by saying

“While women have access to the public sphere as citizens equal with men in

modern Turkey, the private sphere is still held to be the appropriate place for

women, since their roles as mothers and wives are prioritized by the prevailing

patriarchal mentality” (Özman). As recently as March 2016, Turkey’s current

president, Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, said in a speech that a woman “is above all

else a mother” (France-Presse). Places like Turkey are able to maintain

patriarchy through control over female bodies. Power over bodies is an

extremely important way to perpetuate social hierarchies as famous French

philosopher Michel Foucault explains in his work “Discipline and Punish: The

Birth of the Prison.” Some feminists, such as poet Adrienne Rich and activist

Andrea Dworkin, also discuss power over bodies and how it is a way that males

maintain dominance over women (Bordo). What makes Mustang such a unique film is how it skillfully presents ideals

similar to Rich. Foucault, and Dworkin’s without ever once mentioning politics

or feminism. As Adile Sedef Dönmez states in a review of the film, “The movie

explores women’s issues by focusing on social and private life, rather than

structural and legal problems, and through this delineates the way these

oppressive structures are recreated within the family and society.” The

politics of a nation are often an abstract concept to many people and the ways

in which they affect the family unit is where they truly play out. Thus, the

focus on the family in the film puts the issues of control and dominance over

women’s bodies’ in the viewer's face in a very real and approachable way.

The

catalyst for all the action throughout the film is the scene where the sisters

play in the ocean with the school boys. The reaction to this incident shows how

the town, the girl’s uncle, and their grandmother all attempt to exert control

over the sister’s sexuality. According to Rich, denying women their sexuality

by means of punishment is another method by which “male power is manifested and

maintained” (1596). After the ocean

incident, the uncle is angry with the grandmother for allowing the girls to

interact in a potentially sexual way with the young men. The grandmother keeps

trying to reassure him that they have done nothing wrong to which he replies,

“If they’re sullied it’s your fault!” (Ergüven). Thus, the sister’s sexuality

is deemed to be under the control of the uncle and the grandmother and not the

young women themselves. Foucault

discusses the modern invention of institutions that discipline the body. He

mentions a French prison named Mettray as an early model for these types of

institutions. He explains that one of the hierarchical models in which inmates

were divided at Mettray was a ‘family’ structure. The prison’s task was “to

produce bodies that were docile and capable” using family models among others (1491). In a similar way, the sister’s family hierarchy

is an institution that controls their bodies. Their grandmother is expected to

produce docile young women that adhere to patriarchal norms. The grandmother

reassures the uncle that the sisters are still virgins despite their play in

the ocean by saying “I’ll prove it to you” (Ergüven). Again, it is the

grandmother and uncle’s decision to subject the three older sisters Ece, Sonay,

and Selma to a “virginity report,” which is a direct violation of their

bodies. According to the article

“Virginity Examinations in Turkey: Role of Forensic Physicians in Controlling

Female Sexuality” these tests are “gynecologic examinations that attempt to

correlate the status of the hymen with the occurrence of sexual intercourse”

because “rupture of the hymen is considered evidence of loss of virginity”

(Frank). This article also goes onto to assert that “premarital female

virginity is considered an important social norm that may serve to control

women's behavior” (Frank). Thus, at the beginning of the film it is established

that the young women do not have much control over their own person due to the

patriarchal control that the authority figures in their life exert over them in

a prison-like fashion.

Another

demonstration of how male patriarchy maintains control over women is conveyed

in the film through the uncle’s molestation of Nur. The film tackles this

somewhat delicately by not showing any actual molestation, but strongly

implying it. Lale sees the uncle quietly sneaking into Nur’s room at night, and

then the next scene cuts to Lale waking up to her grandmother and uncle

arguing. The grandmother exclaims “What were you doing? I asked you a question!

Stop that! Stop it right now!” (Ergüven). This scene makes it clear that the

uncle feels he has complete control over the sisters, which includes sexual

access to them. Rich describes this type of behavior as forcing male sexuality

upon women by means of rape or incest (1549). Rich sees this as another form of

power that men hold over women to enforce patriarchy. Their grandmother’s reaction to the

molestation only serves to reinforce this power structure. Their grandmother

does not turn their uncle into the authorities despite being appalled by his

actions. Instead she begins plans to arrange a marriage for Nur since she, “is

a young woman now” (Ergüven). The

grandmother is again acting as an agent of patriarchy and using the sisters as

“objects in male transactions” (Rich 1595).

She is transferring ownership of the young women’s bodies from the uncle

to another male. Their grandmother is not encouraging the girls to embrace any

personal control. Dworkin explains the behavior of women like this in her

speech “Terror, Torture, and Resistance.” She discusses how some women accept

as a basic premise of life that women are “things” that must be sexually

pleasing to men to survive. Thus, women in oppressed situations are often brave

people, but they use their bravery to make deals that compromise their freedom

in the name of survival “instead of fighting the system that forces [women] to

make the deal” (Dworkin). An arranged marriage to protect a young woman from

rape is an example of this type of “deal.” The grandmother feels she is being

brave when she is an active participant in the young women’s oppression.

Ece

and Lale both rebel against the patriarchal structure of Turkish society in

very different ways. Ece takes control over her body by committing suicide. The

scene begins with the three youngest sisters eating dinner with their uncle and

grandmother. The uncle is intently watching a television program. The audience

does not see the television, only the uncle’s face as he is absorbed in the

program. The voice on the television states, “Women must be chaste and pure,

know their limits, and mustn’t laugh openly in public, or be provocative with

every move. Women must guard their chastity!” (Ergüven). The faceless man on the television is

explicitly encouraging the control over women’s sexuality that Rich has

described. Ece makes fun of the program

by putting up her middle finger in front of her face where the other two girls

can see, and they all begin giggling. As a result, the uncle demands that Ece

leave the table. When she goes into the room, she shoots herself. It is clear

that Ece is fed up with the patriarchal attitude of both her uncle and the

surrounding society. She feels that the only way she can exert control over her

own being is to end her life. Ultimately, Lale exerts control over her

situation, much like Ece did, but in a much more constructive way. At the end

of the film, on what is supposed to be Nur’s wedding day, Lale initiates a

daring escape from the house with Nur. She locks the entire wedding party out

of the house while her uncle bangs angrily on the doors and windows trying to

get in. The two girls manage to escape and eventually make it the more

cosmopolitan city of Istanbul where they find their female school teacher and

show up at her door. Lale’s daring

escape echoes the words of Dworkin in “Terror, Torture, and Resistance” when

she says: “ I'm asking you to fight…I'm not asking you to get caught. I'm

asking you to escape. I'm asking you to run for your life” (Dworkin). Dworkin

is encouraging women trapped in violent and oppressive situations to stand up

for themselves through escape rather than death, and this is exactly what Lale

does. Lale exerts ultimate control over her body by getting away from both her

uncle and the arranged marriage. She does not compromise her freedom by

allowing herself to be transferred to another male in order to avoid

molestation from her uncle. She then seeks out the help of an educated woman in

a metropolitan city as her final act of defiance in the film.

It

is clear that Ergüven wanted to discuss feminist issues with her film Mustang. Ergüven explains in an

interview that she “had long had an abstract desire to tackle the question of

what it is to be a woman in Turkey” (Cooke). Ergüven brilliantly conveys a

powerful message regarding the enforcement of patriarchy through control over

women’s bodies. These ideas are reminiscent of the work of great writers like

Foucault, Rich, and Dworkin. A mustang is a wild free-roaming horse, and the

film’s title acts as a symbol for the free spirits of the sisters that

authority figures attempt to tame throughout the film. However, at least two of

the sisters are able to break free from their oppression thanks to the

untamable strength of the youngest sister Lale. This strength is a powerful

role model for women dealing with oppression that encourages them to fight and

to escape.

Works Cited

Bordo, Susan, and Monica Udvardy.

"Body, The." New Dictionary of

the History of Ideas, edited by Maryanne Cline Horowitz, vol. 1, Charles

Scribner's Sons, 2005, pp. 230-238. Gale Virtual Reference Library, Accessed 11

Dec. 2016.

Cooke, Rachel. “Deniz Gamze Ergüven:

'For Women in Turkey It's like the Middle Ages'.” The Guardian, Guardian News and Media, 15 May 2016.

Darity, William

A."Patriarchy." International

Encyclopedia of the Social Sciences, 2nd ed., vol. 6, Macmillan Reference

USA, 2008, pp. 173-174. Gale Virtual Reference Library, Accessed 11 Dec. 2016.

Dworkin, Andrea. “Terror, Torture,

and Resistance.”Canadian Woman

Studies/Les Cahiers de la Femme, fall 1991, Volume 12, Number 1.

Dönmez, Adile Sedef. "Mustang

(2015)." Nidaba 1.1 (2016): 84. journals.lub.lu.se/ojs/index.php/nidaba/article/download/15853/14340

Ergüven, Deniz Gamze, director. Mustang. Cohen Media Group, 2015.

Frank MW, Bauer HM, Arican N, Korur

Fincanci S, Iacopino V. “Virginity Examinations in Turkey: Role of Forensic

Physicians in Controlling Female Sexuality”. JAMA. 1999; 282(5):485-490,

Foucault, Michel. “Discipline and

Punish: The Birth of the Prison.” The

Norton Anthology of Theory & Criticism. Ed. Peter Simon. 2nd ed, New

York: W.W. Norton, 2010. Print.

Schafer,

Elizabeth D. "Mustangs." Dictionary

of American History, edited by Stanley I. Kutler, 3rd ed., vol. 5, Charles

Scribner's Sons, 2003, p. 504.

Özman, AylIn. "Turkey." Encyclopedia of Women & Islamic Cultures,

edited by Suad Joseph, vol. 2: Family, Law and Politics, Brill Academic

Publishers, 2005, pp. 670-671. Gale

Virtual Reference Library.

France-Presse, Agence. “Recep Tayyip

Erdoğan: 'A woman is above all else a mother.'” The Guardian News

and Media Inc.

Rich, Adrienne. “Compulsory

Heterosexuality and Lesbian Existence.”The

Norton Anthology of Theory & Criticism. Ed. Peter Simon. 2nd ed, New

York: W.W. Norton, 2010. Print.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)